“Rola Fua” by Krishna Bhaskar is a charming and tender tale of a legendary family matriarch—tiny in size, mighty in spirit, and a certified queen of triple takes. Through repeating phrases, parrots with bedtime routines, and dreams of Patna, this story wraps nostalgia, humor, and love into one beautifully old-school package.

Fua was the term used for dad’s sister or dad’s female cousins. Well, Rola Fua wasn’t an ordinary fua. She was quite an interesting lady.

Rola Fua wasn’t my aunt. She was my Nana Ji’s aunt—meaning, my maternal grandfather’s aunt. So, Grandpa called her Rola Fua, my mother called her Rola Fua, I called her Rola Fua, and apparently a lot of people called her Rola Fua. There weren’t proper Hindi terms for great-grandparents or great-grand-anything, so people just used whatever the elders said.

One thing about Rola Fua was well known to everyone—she repeated everything thrice. Things like, “E saal matar ke chokha na khayli he, e saal matar ke chokha na khayli he, e saal matar ke chokha na khayli he” (meaning, “This year I haven’t had mashed fresh peas” × 3).

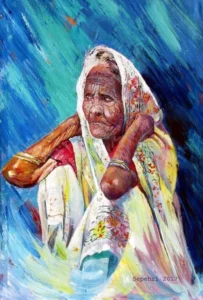

The way I remember her, she was a tiny, tiny old woman curled up like a toe ring. She was born in the early 1900s, probably around 1910 or 1915. We didn’t have a tradition of remembering birthdays back then. No one had a calendar, and birthdays weren’t really a thing.

People usually referenced their birth time or date with a big catastrophe. Often, you heard people say, “I was born in the year of the big flood.” Some would say they were born in the year of a big earthquake that shook the village temple’s bell all night. The wise guys would instantly pull a joke—“You were such an idiot, God was giving a warning of your birth by ringing that bell.” Usually, the guy made fun of had a none-to-mediocre comeback.

I don’t know the big catastrophe reference with Rola Fua’s birth at all, neither does anyone else exist who would remember.

She was a chatterbox. She talked all day long, times three. She would leave her house as soon as she could and go chit-chatting with neighbors, drink multiple rounds of chai, snack on, but make a quick trip home to eat main meals. Eating the main meal at someone else’s casually wasn’t a thing to do back then.

Mom says Rola Fua was no less than a fashion queen of modern times. Her entire focus was clothes, jewelry, and makeup of that time. Even in her old days, her velvet blouse had glasswork. Pure gold jewelry just loaded on her tiny body.

She wasn’t able to afford her fancy life by accident. She asked for it and got it. Her dad was a successful farmer with a big house, many staff, a bunch of cows, and tons of grains in storage.

Once, he decided it was time to upgrade his vehicle—his horse. The tiny rivers would often flood during monsoon time and horses would get nervous crossing in neck-deep water. Elephants didn’t. It was time to buy an elephant. Well, the big carnival, Sonpur Mela, was around the corner.

For over a century, Sonpur Fair has been known as the biggest fair in Asia for animal trades and transactions. From parakeets to parrots, from hamsters to elephants, squirrels to bears, clothes to jewelry—you could buy anything there. Heck, many found their soulmates there. The wise guys of the villages and the priests (pundits) would sit under the big trees with potential candidates for marriage. They would make matches, and many would get married or at least engaged under that tree. Those marriages would last a lifetime, unlike the well-vetted ones nowadays. When you start with no expectations, you run into fewer problems. Interesting, isn’t it?

Daughters have known the way to win their dad’s heart since the beginning of time. She was probably ten years old. The moment she heard of her dad going to Sonpur Mela, she would walk behind Daddy, blinking her eyes in cuteness saying, “Daddy, I want to go with you. Daddy, I want to go with you. Daddy, I want to go with you.” So, Daddy’s little heart melted in love and they left on their trip to Sonpur.

From the village to the state capital, Patna, and then across the big river Ganga on a small ship or big boat. They called those boats “steamers”—I don’t know why. Something to do with steam, maybe.

They stayed overnight in Patna at a relative’s place before boarding the boat to Sonpur. This was the first time Rola Fua had seen electricity. This was the first time she had seen many things—light bulbs, switches, ceiling fans, big roads, roundabouts, city buildings, shops and fancy markets, people walking beautiful dogs, etc. etc. etc.

The dogs in the village never had fur; the dogs in the city didn’t have the freedom to walk on their own—but they were damn cute.

It was love at first sight. Rola Fua had fallen in love with Patna.

She made a commitment and kept it in her heart.

She made a commitment and kept it in her heart.

She made a commitment and kept it in her heart.

Was it fun at Sonpur Mela or was it fun at Sonpur Mela? She made her dad buy her all kinds of things: a dancing man made of dried palm leaves—you twist the little stick and the hands and legs would fly up and down. A red drum on a stick—you just keep moving it and it would make a drum beat noise. Bangles, balloons, animals made of clay, a clay elephant.

Speaking of elephant—the real elephant was purchased. How can you even write about the level of amusement of a child whose dad just bought a real pet elephant? And then, the elephant’s transportation on the mini-ship and the return journey to the village. All was like a dream.

There was a much bigger dream ten-year-old Rola Fua had deepened in her eyes, brain, and soul though. She would tell when the time came.

Years went by. Monsoons came and went. Seasons of making paper boats, eating raw mangoes, finding guava with the red pulp, getting henna on palms and legs kept her entertained for the next few years. Many cows in the house had cute little calves. Time flew and she was fourteen. This was the early 1900s.

Dad started to look for boys who were from wealthy farming families. Rola Fua’s mom broke the news while making snacks with fresh jaggery. She said, “Dad is looking for your groom. You will be married soon.”

She didn’t know how to react, but she knew time had come.

She found Dad alone in the garden. He was cherishing the plants loaded with eggplants and tomatoes. Radishes too.

She said,

“If I get married, make sure the guy lives in Patna. I want to live in Patna.”

I want to live in Patna.

I want to live in Patna.

So, she got married into the famous Mauar family in Patna—a rich, entrepreneurial family settled in the old side of Patna. Her husband was a good-looking guy, just a year or two older than her. He loved her dearly and bought her whatever she wanted. She had the big, giant silver keyring with a peacock made of gems—and most importantly, all the keys. Keys for everything they owned. She lived in a big, giant house with outhouses and big trees. Monkeys often sat next to her trying to steal her combs and mirror. She would repeat, “As long as you don’t steal my jhumkas (earrings).”

Everyone got married at a young age, but they stayed separated at their own homes till they were in their late teens or early twenties. The system knew how to care for their daughters. All of this sounds strange in today’s date, but it was well designed—so well thought out for that era.

Marriages were at a young age to eliminate distractions, but you only lived together when you were prepared mentally and physically. Matches were made after many layers of due diligence—much, much, much better than a pumping heart would do on its own. I am glad we don’t marry our daughters or sons so young anymore, but can’t help to not notice when love and care scrutinized and regulated the traditions in history.

When I was a teen, I was often sent to deliver seasonal delicacies and mom-made pickles for Rola Fua. It was only a ten- or fifteen-kilometer journey, but it would feel like 40 since I was young and my 43cc moped didn’t have any strength. I had ruined the engine by giving fun rides to my friends.

Rola Fua’s eyes would light up hearing my mom had sent her things. She would be sitting curled up on an old British-style chair with an adjustable wooden frame and a carpet-like back and bottom. She had a hand fan by her even though she had the ceiling fan. Village doesn’t go away when you go away from village. She still kept her habits and things from the village. She would say the ceiling fan is for the guests—she preferred the hand fan made of palm leaves.

She would tell me to tell my mother she really waits for these deliveries. Then she would emphasize me conveying the message that she was worried that this year Malti (my mother) had forgotten about sending the khat-mithhi, a mango marmalade made of fresh raw mangoes.

About ten years ago, Rola Fua passed away. I happened to be visiting India and decided to visit her family for condolences.

After my visit, I was walking out of her verandah towards my car, and I heard her parrot talk to herself in a low-medium voice—

“Rupu is tired, it’s time to take a nap.

Rupu is tired, it’s time to take a nap.

Rupu is tired, it’s time to take a nap.”

Rola Fua had named her parrot Rupu. I smiled and choked on emotions at the same time. I got in the car and didn’t turn on the music. Life itself is a song. If you have the right headphones, you can hear it and enjoy it.